在处理性能问题的时候,需要知道客户请求都堵在哪儿了。

具体说,有这么两个需求

-

能够知道客户请求阻塞在什么地方了。比方说,最好能够列出当前还没有完成的请求都是什么状态。是在等 osdmap,还是在等 PG,还是在等它希望访问的 object?

-

提供一个机制,能阻塞客户请求。我们有时候甚至希望有计划有策略地阻塞客户端请求。实现一些 QoS 的功能。

Crimson 为了解决这些需求,引入了一组概念

Operation-

代表一种操作。比如说刚才提到的客户发来的请求就是一种

Operation。 Blocker-

代表处理操作的一个特定的阶段。像刚才提到的 “等 osdmap”,就可以作为一个

Blocker。 Pipeline-

代表系列

Blocker。在做限流或者 QoS 的时候,pipeline 也是一个资源。

为了集中跟踪当前的 Operation ,我们定义了

ShardServices::start_operation()

,用一个全局的数据结构分门别类记录各种操作。这里以简化版的

ClientRequest::process_op() 为例,解释一下用法

seastar::future<> ClientRequest::start(PG& pg)

{

return with_blocking_future(handle.enter(connection_pipeline().await_map)

).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(osd.osdmap_gate.wait_for_map(req.min_epoch));

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(handle.enter(connection_pipeline().get_pg));

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(osd.wait_for_pg(req.spg));

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(handle.enter(pg_pipeline(pg).wait_for_active));

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(pg.wait_for_active_blocker.wait())

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(handle_enter(pg_pipeline(pg).recover_missing));

}).then([&] {

return maybe_recover(get_oid());

}).then([&] {

return with_blocking_future(handle.enter(pg_pipeline(pg).get_obc));

}).then([&] {

return pg.with_locked_obc(get_op_info(), [&] {

return with_blocking_future(handle_enter(pg_pipeline(pg).process)).then([&] {

return process(req);

}).then([&](auto reply) {

return conn->send(reply);

});

});

});

}处理一个请求有多个步骤,它们构成一条流水线

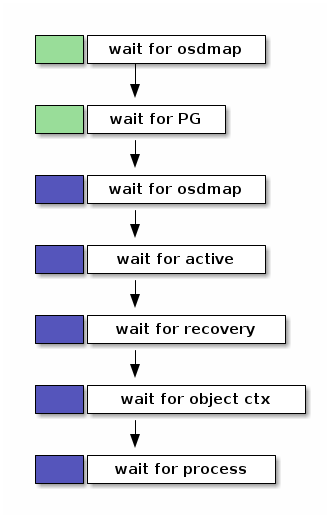

其中,绿色和蓝色分别代表一条小流水线。

-

绿色的是 connection pipeline。每个客户端来的链接都有一条。它分两个阶段

-

wait until osd gets osdmap

-

wait for PG

-

-

蓝色的是 PG pipeline。每个 PG 都有一条。

-

wait until PG gets osdmap

-

wait for active

-

wait for object recovery

-

wait for object context

-

wait for process

-

一条流水线就像博物馆的一层楼。流水线分多个阶段,每个阶段就像一层楼里面的一个个展厅。第一次去一个博物馆或者艺术馆,我一般会拿着小册子,按照顺序,一个展厅一个展厅地逛。因为不会分身大法,所以也没办法同时在几个展厅参观。这个设定和 Ceph 处理客户端请求是很像的。但是即使是在疫情期间,博物馆的展厅也能同时容纳不止一个人。那么这些 pipeline 呢?在同一时刻,我们允许多个请求停留在同一阶段吗?

答案是“不可以”。

blocking_future<>

OrderedPipelinePhase::Handle::enter(OrderedPipelinePhase &new_phase)

{

auto fut = new_phase.mutex.lock();

exit();

phase = &new_phase;

return new_phase.make_blocking_future(std::move(fut));

}其中 new_phase 就是即将进入的新展厅:

class OrderedPipelinePhase : public Blocker {

// ...

seastar::shared_mutex mutex;

};

要是不熟悉 seastar::shared_mutex,可以把它理解成和

std::shared_mutex

有类似语义的共享锁。但是这里调用的是霸气的

lock() 而不是

lock_shared()

。所以在别人离开展厅之前,你是没法进去的。同样,要是你在里面,别人只能止步。

这个气氛好像很不和谐。就像好多人希望去一个很大的展厅,他们想看的展品其实都不一样,但是因为里面已经有 一个人 了,所以大家只能依次在门外排队,等出来一个人,才能进去一个人。这个情形倒很像是高峰时段的厕所。

如果有多个不同的请求正好访问同一 PG,即使它们对应的是不同的

object,也不得不互相保持二十米的距离,挨个等待

PG.client_request_pg_pipeline.process

。前面一个人不完事儿,后面的人必须等着。

这不又是 PG 大锁嘛。我在例会上提出来这个问题。Sam 提醒我。可以从另外一个角度看这个问题。每个 OSD 都有上百个 PG,而一个集群有成百上千个 OSD。如果 PG 的分布很均匀,那么每个 PG 同时需要处理的请求其实是不多的。而且,我一直有个误解,就是觉得 PG 大锁是现有 OSD 性能不彰的原因之一。但是 Sam 告诉我,问题不在于 lock contention,而在于 CPU 的使用率居高不下。这才想起来,官方的文档建议一个 OSD 一般需要配备两个核。

不过还是有点放不下心,最好我们能在各个“展厅”前面设置一个计时器,看看大家都在门外面等了多久。这也是流水线机制设立的一个初衷。